“While you slept, the world changed.”

This was the promise Jonathan Hickman made to us, through the words of Charles Xavier, from the very beginning of House of X, that things were going to be different from here on out. Gone are the X-Men we know, and here to stay is a new status quo…and if there is anything that X-Men #7 has proven…it’s that he intends to follow-through with that promise. No holds barred.

Now, the general reaction I’ve seen online to, not just this issue, but the entire Dawn of X era as a whole, has been fairly mixed. Although it seems like a general consensus has tended to lean more towards the “positive” side, the one thing that people on both sides of the fence can agree on is that it certainly is different.

In this new age, the X-Men have evolved to be more mutant than ever. By that, I mean that they are no longer just another one of Earth’s super-hero teams. Where there used to be a time when the X-Men name would have been used in conjunction with say the Avengers or the Fantastic Four when discussing their role in the Marvel Universe, that time has passed. And for many people, Issue #7 of the 2019 X-Men series by Jonathan Hickman, Leinil Francis Yu, and Sunny Gho provided that final nail in the coffin. The biggest sign yet that those times are gone…the X-Men are dead, long live Krakoa.

To give a short synopsis of the story, for anyone who wandered in here out of sheer curiosity or to those who might need a refresher, X-Men #7 is the story of a trial by fire. We start the story by picking up with the Guthrie family on the island of Krakoa, the new safe haven for all of mutantkind. Specifically, we’re following Melody Guthrie, once a mutant with the ability to fly called Aero (not to be mistaken with the new Agents of Atlas character). She lost this ability on M-Day, the day when Wanda Maximoff, the Scarlet Witch, robbed 99% of Earth’s mutant population of their powers with three spoken words. Since then, many mutants have regained their powers, but Melody is not one of them. But today, it seems that they’re ready to change that, as Melody is informed that she’s been chosen for something called “The Crucible”.

While Melody is getting ready, we spend the rest of the issue following Scott as he tries to come to terms with what’s about to happen during “The Crucible”. And this leads him into a bit of soul-searching with Wolverine and Nightcrawler

We get the impression, during these interactions, that whatever is about to happen during this ritual, as they call it, is a bit controversial around the island, with some like Wolverine wishing to avoid it altogether…

And causing others, like Nightcrawler, to question deeper things about themselves, including their faith. Which, for a character like Nightcrawler who has always been depicted as devoutly Catholic, is a huge prospect for any long-time fan of the X-Men franchise.

And when we learn about what the Crucible is, it’s an understandable reaction. It’s a ritual of self-sacrifice, of death and rebirth. For Melody to regain her powers, she must face down Apocalypse, alone…and she has to die.

For anyone really unfamiliar with the X-titles of the last few years, let me summarize one of the most important revelations that’s come out of them. We’ve all joked for years that death in comics doesn’t matter, that anyone who dies will be back in a few issues anyways, and with the X-Men that is now truer than ever before. Hickman took the trope of insignificant comic book deaths and flipped it on its head. It’s no longer a bug, it’s a feature. Using a combination of specific mutants, the X-Men have found a way to resurrect any mutant who has died or who will die. The process is a bit complicated so I won’t get into to details, but just know that as of right now…the X-Men are masters of death.

And this is what leads to the central conflicts in this issue, both external and internal. We see Melody fighting a battle she can not possibly hope to win in the Crucible, while Scott and Kurt have a conversation about what the implications of their new immortality in the stands. And then, in front of almost all of Krakoa, we watch as the fight takes the only path it ever offered. It ends with Apocalypse killing Melody.

But, immediately after, we’re shown her rebirth, in front of all of Krakoa, once again the mutant known as Ero, showing off her powers as she flies into the air, and we get the final line of issue where Kurt tells Scott that he thinks he needs to start a mutant religion.

So, looking back, this issue…is a heavy one, to put it delicately…perhaps the heaviest and most unusual since we watched a handful of fan-favorites like Cyclops and Nightcrawler die and be reborn themselves back in House of X #3, and, from what I’ve seen, the issue has received an understandably mixed reception.

To some, this issue went to far, depicting the X-Men as no longer a group of heroes but instead this insane “cult” that has rejected humanity entirely, cementing this run as a new age for X that they just can’t get behind. Meanwhile, others have praised it as one of the best issues in the run so far, claiming it’s a deeply moving and emotional issue.

So, where do my thoughts on it lie?

To me, quite frankly, this might not just be my favorite issue to come out of the Dawn of X era so far…this might not just be my favorite issue of X-Men I’ve ever read. Period. And to the people on both sides of the debate…I have to say that I think they’re both right. I think this issue helped separate mutants from humanity, but I also think that they did so in an incredibly moving and logical way. Let me explain.

I think to feel uncomfortable while reading this issue is completely natural, and perhaps the response the creative team was expecting and hoping for. The issue tackles some uniquely human themes, and goes against all conventional approaches and understanding of these themes. Those themes specifically: Death and Faith.

It’s the first real time that I think, as readers, we’ve come to truly understand that death…has no sting for mutantkind anymore. We’ve seen several people brought back before (the team that died in House of X, Xavier himself in the X-Force line, etc.), but these were “abnormal” deaths, deaths brought about by an enemy. In short, the kind of deaths expected to be given a comic book resurrection in due time anyways.

Here, it’s no longer a consequence…it’s a price to be paid. It’s like a currency, in a way. It’s something that can be traded. This is the first real time we’ve been forced to ask the question, “When death becomes obsolete, what then is the price of life?”

That’s one of the focal points of Nightcrawler and Cyclops’ conversation during the Crucible. Even if death is meaningless, isn’t violence to one’s self still violence? Is violence for the sake of violence not still wrong because it has no consequence? Because that’s what the Crucible is, it’s violence. Violence with a purpose, but violence.

And purpose is a clear point to keep in mind, because another question brought up is basically, “If we’ve conquered death, and we can restore a mutant into a body that’s even better than before, what’s to keep people from just…killing themselves to make themselves better?” Because you’d imagine, for the millions of mutants around the world who were victims of M-Day…the prospect has to be enticing.

Hence, the reason for the Crucible. It’s the mutant council saying, “Yes, we can give you your powers back, all you have to do is die…but you have to earn it. You have to prove that you’re willing to fight for it, you want these powers, you’ll die for Krakoa and for your people.” It’s a process designed to not only avoid pointless, needless death, but also to make sure that the strength of the mutant society that they’ve just finished creating remains strong. It’s essentially a hazing ritual that anyone who was a member of a sorority or fraternity in college could probably relate to. It has practical, and symbolic, purpose.

Even for a people to whom death is no longer a permanent end, but rather, no more inconvenient than a dislocated shoulder, it shows that they’ve moved past it…but not beyond it. It simply plays a different role within their society, within their lives, rather than simply signifying the end of it. A concept that, as a human, seems alien, scary, and makes us uneasy. It’s unnatural.

And one of the best parts of this issue is that you see that within the mutant community on Krakoa, the Crucible makes them uneasy as well. Why wouldn’t it? Even though the start of Krakoa symbolizes a new step in the evolution of mutantkind, the genesis of their own shared heritage, most of those mutants on Krakoa were born to human parents, once knew human lives. Basically, for all their history, the only thing that really set mutants apart from humanity was a few differences in their DNA and a handful of super-powers. As a people, they were literally no different than the humans they lived among.

So now, things are different, and we’re seeing that every mutant is taking to these changes differently. With some embracing them, with literally everything to gain, like Melody, and others feeling more reserved and uneasy about it, like Wolverine and Nightcrawler. Because to talk about death, you have to bring up the question of faith, and that’s such an innately human topic that is so personal that most would rather avoid talking about it.

The reason for this being that faith and death are so closely linked in so many different human cultures. Just about every religion has their own concept of the afterlife, about what happens when we die, and how to live your life to achieve the best possible outcome. So, what happens to your faith when the concept of an afterlife becomes obsolete? This is the central internal conflict for the story, and we see it all through Kurt’s perspective, and what better character to choose?

Religion ties deeply into a lot of X-Men characters, but arguably none more so than Nightcrawler, a character who, throughout all the hardships in his life, consistently felt a sense of belonging and comfort within the Catholic church. So, naturally, he makes the perfect vessel for a lot of the unease and uncertainty that we, the reader, are experiencing along this journey, too, as he questions just what exactly is right and wrong anymore. Especially troubling when many people derive their moral codes from the faith they adhere to, and since most of those faiths revolve around the purpose of life and death, you can start to see how one simple concept (the idea of easy resurrections) could start a domino effect that would start to challenge so many core concepts of this new society. There is no one more conflicted on the entire island of Krakoa right now, than Kurt Wagner.

And we follow this journey that he undertakes spiritually through the entire issue, asking hard questions, only to realize that the more he asks, the more he tries to seek answers within the faith he’s had his entire life…the more questions he has…which makes sense because how could it be any other way? As Kurt says himself, “Why seek heaven if we can–for all time–do God’s work here in the living world?” His faith has no answers for him, because he no longer fits inside it. He no longer fits the mold. Thinking about heaven is no longer a logical concept, because he’ll never die. So, where does that leave him?

It takes him to the only logical place left for him to go, if his faith no longer fits him…then he’ll make one that does. A departure for the character? Perhaps, in the broadest of terms, but arguably the only one that made sense, and one I feel was earned and still stays very faithful to who Kurt Wagner is.

As seen in this issue, the moral and spiritual implications of resurrection on what equates to basically an assembly line could easily fill a book of questions if such a thing existed, so it feels like a natural progression for the most religious man on all of Krakoa to be the one who realizes that they need this…not just for himself…but for everyone. I saw this not as Nightcrawler abandoning his faith, abandoning his religion, but simply, like the rest of his people, evolving along with it. Religions evolving and changing with the times for what a certain people need is something incredibly common (spoken like the true Protestant I am), and it’s a much deeper discussion than most comics are openly ready and willing to have, and I think it’s one of the most exciting and refreshing aspects of this new age of X.

But, while exciting, redefining these terms–death and faith–Hickman is walking a delicate line. For almost 60 years, these characters have been our heroes. Like I said earlier, once they seemed just as human as we are, and by taking them to Krakoa, by developing this new culture, this new status quo, I think one of the biggest challenges Hickman has faced so far, and, admittedly, what put myself off these books for such a long period of time, was the risk of “othering” the mutants.

See, this comparison has been made a few times now, but what’s happening with the X-Men right now has drawn some parallels between them and another Marvel IP that has had its fair share of comparisons and run-ins with the X-lines before: the Inhumans.

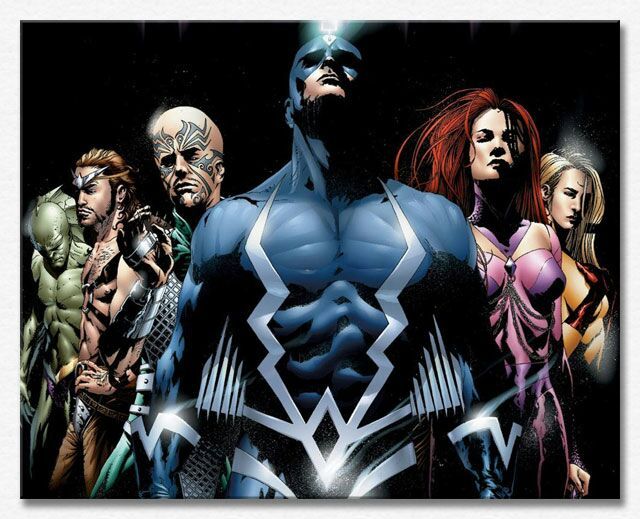

See, the Inhumans and the X-Men shared a lot of similarities, especially during the Marvel: NOW! and All-New, All-Different eras of imprints. Both were human mutates who developed extraordinary powers and bizarre, otherworldly appearances, and both have been victims of humanity’s fear and prejudice. Yet, one of the aspects that always seemed to separate the Inhumans from the mutants was their level of “other-ness”.

Whereas the mutants lived among humans, were born among humans, the Inhumans were a society onto themselves, mostly hidden and secluded from the rest of the world, sometimes that was meant literally…like as in the moon. In short, they were not like us. Inhumans had a much more fantasy/sci-fi feel that way, feeling more like another race in and of themselves than an offshoot of humanity. They had their own civilization, their own culture and traditions (including a unique “coming-of-age” ceremony that gave them their powers), even their own unique hierarchy that extended beyond Earth and into space through branches of “sister” Inhuman colonies on other worlds. While still relatable and intriguing characters, Inhumans were often not “human” characters with “human” experiences.

The mutants never had anything like that. Even during the times in the past where mutants tried to separate themselves from humanity, like on Genosha or Utopia, we never saw much change in who the X-Men were at their core. They still felt human. They acted like humans, they liked human things, they held human beliefs. So, no matter how far away they were…they still felt human, and that makes them more relatable. Which, was part of the point of the X-Men for the longest time, showing us the ugliness of prejudice against people who look or were born different than us.

I’ve seen many people talk about why the X-Men became so popular, and why the Inhumans never seem to stick, and I’d imagine a lot of it has to do with the fact that readers can put themselves into a mutant’s shoes a lot easier than they can an Inhuman. Generally. (There are plenty of exceptions, especially since the All-New, All-Different days when Terrigen was released globally and we saw Inhumans born from outsiders for one of the first times ever.)

So, now we’re at that thin-line. The question is: how do you redefine what it means to be a mutant, without taking away what makes them (pardon the phrase) “human”? How do you do that without othering the X-Men? How do you make the same characters we have loved for decades immortal…but still relatable?

It all comes down to–again, pardon the phrase–the execution.

I think there are very few teams in the industry today that could have pulled this issue off, and I mean that with full-sincerity. The tactfulness that Hickman handles this script, and the action of the characters, and the adept way that Yu conveys the perfect emotion in every panel is a masterclass in visual storytelling.

Let’s talk about Hickman’s side-first, taking a close look at the way he handles the story.

First, I’d like to praise the anthological style Hickman has adapted when it’s come to this mainline X-Men series. I think it’s a style that suits him, and it’s a style that, reading his other works from Fantastic Four to X-Men he seems to prefer. Instead of focusing on different arcs that link together like individual movies in a saga, Hickman treats each issue almost as it’s own, self-contained story, that, when all is said and done, fits together with all the others like the snug pieces of the puzzle, revealing that, all-along, everything was just a part of a handful of real major movements. It allows for a bigger story to play out in unexpected ways, an it allows for smaller stories, like this one, to be told along the way without interrupting the flow of the overall narrative.

Because this story, even though it feels, at first glance, entirely separate from the stories that came before and after it, adds quite a bit to the main plot in terms of raw world-building. There are few writers that I can think of that can world-build better than Jonathan Hickman (Everything is connected, everything matters, I hope you’re taking notes).

Besides the fact that entire issue was dedicating to redefining mutant culture (perhaps just defining it for the first time), this issue gives us plenty of other bits to chew on as we go.

We get to see the relationship budding between Cyclops and Wolverine, something we never thought we’d see (especially not to the degree that we’ve seen here that many have interpreted as openly flirtatious and romantic), and we get this scene that feels almost inconsequential of Nightcrawler discussing a shimmering tower that only he can get inside that he feels was almost made for him.

While both of these scenes feel almost throw-away in terms of the story as a whole, certainly compared to the gruesome and barbaric spectacle that is the Crucible, I think they’re meant to help service the notion that Krakoa really is perfect…old enemies are now friends (perhaps more)…

And these people, who once fit in nowhere, now feel like they have a place meant solely for them. Whether this peace is all a cover for something more diabolical underneath or if this peace could ever hold, I can not say (although I doubt it), but for now, it’s letting you know that things…are feeing pretty good…and for long time fans of these characters…the idea that they have found this true happiness, no matter how brief it may be, is certainly a reassuring thought. Surely one that helps keep them grounded and “human'” in our hearts, all before the big questions and reveals start coming down.

I also think, on the opposite end of the spectrum, while still in service of retaining the X-Men’s “humanity”, it’s very smart that Hickman leaves two of the more extreme roles here in the hands of former villains.

We see this almost sinister campfire lesson between Exile and a handful of unknown mutant children in the woods where Exile explains what M-Day was and what the Crucible is to a bunch of children, and we see that this younger generation is already starting to distance themselves from the humanity that the other X-Men saw during their youths. This is the first generation of mutants to grow-up on Krakoa, and they’ve all already seemed to adapt these ways as a sort of religion. They recoil at the name of the Scarlet Witch like she were Satan himself, and they repeat these mantras like “No More” and talk about the inevitable bloodshed and death at the Crucible as if it were completely normal.

A moment that Scott and Kurt witness, but say nothing of. It feels like an indoctrination, and moments of it do feel a bit hostile, and there’s another moment that Exile shares with these same children (I believe) a few issues down with Magneto that has a similar hostile feel to it. (Just as an aside, everyone’s saying that they don’t trust Apocalypse, but I think Exile’s the sketchy one, I think we should keep our eyes out for him and these kids as we go down the line)

Speaking of Apocalypse, I think it was also a wise move to make him the opponent faced in the Crucible. What happens there is already enough to make a reader uneasy, but could you imagine the scene if one of the X-Men was the one to face a fellow mutant down? Xavier himself? Wolverine? Psylocke? Between this and the campfire scene, we’re shown that some of the more extreme aspects of Krakoa and this mutant society are stemming from some of the most dangerous foes the X-Men have ever faced, and I think this was smart and intentional. Showing villains on the other sides of these scenes helps keep the X-Men “Good” in the eyes of the readers. They’re a part of this, but it’s much more acceptable that a villain is doing villainous things rather than a hero, even though everyone is supposedly on the same side now. And they even directly hint that Apocalypse was the one who advocated for the Crucible to begin with, give the text over his head when he first appears in the arena.

And another quick little aside, I want to point out that I don’t think there’s anything villainous about this scene at all. Personally I think it’s a triumphant, beautiful scene (for reasons I’ll get into in a minute), but considering it’s more shocking nature I think this decision was made to make it easier for us to accept. I think if it had been anyone else at the end of that blade, the scene wouldn’t have felt the same to me.

Beside that, it’s everything you’d expect from a Hickman story. Masterful dialogue, plenty of cool foreshadowing (Lot of emphasis on swords here, a common motif, I wonder why…wink wink…plus our first look at Warlock and Cypher, a drop that’s already paying off in X of Swords). The issue is paced beautifully, keeping the build-up to the fight entirely tense and gut-wrenching, leaving the fight the right length, not too quick, long enough to be meaningful and get the point across, but not long enough as to be too indulgent or brutal. The characters are given the respect and reverence they deserve.

Then, there’s Yu’s art which I think subtly and subconsciously sold this issue for me. If I were to describe this issue in one word, that word would be “Beautiful.” I’ve heard other people describe it in one word as well. “Triumphant”, “Happy”, “Sad”, “Depressing”. All of which make sense to me, because they’re emotional answers, and this issue BLEEDS emotion. And it’s all thanks to Leinil Francis Yu’s artwork.

It’s all so perfectly subtle that I almost didn’t recognize it all the first time I read through. From the tears in Melody’s eyes at the start of the issue, to the moment she’s left hunched over, stammering in obvious, overwhelming pain, before she stands, resolute and unyielding, to face her foe. From the angry, screaming faces of the Guthries in the crowd as Apocalypse lifts his blade, with Husk tearing off her own skin and with others having to hold Cannonall back, to the look of pure bliss and relief on Melody’s face as she is reborn.

To reflect the conflict inside of him, Kurt’s usually striking, yellow eyes are hidden in shadow almost entirely until the moment they enter the arena, perhaps illustrating the conflict of faith inside him that eventually comes to resolution after witnessing the trial by fire. And the incredibly unexpected and almost humble, remorseful way that Apocalypse’s head is almost continually bowed in solemnness throughout the entire fight, I think it all goes a long way to making you feel something, anything by the time the issue’s done.

And, maybe I’m making a mountain out of a molehill, but I really think the subtleties of the art deserved their own moment of appreciation.

Which brings me to the most emotional part of the issue for me, because even though I think it’s a splendid and uniquely fascinating issue on its own merits for every reason I’ve listed here and more, upon re-reading this issue something hit me a little bit harder than expected. I felt the emotions a bit stronger the second time through, to a point where I actually found myself on the verge of tears. But I wasn’t sure what had changed. What did I miss the first time that clicked now? Why had this issue, specifically the moment inside the Crucible become so intimately personal to me.

And, then I realized why…and I wanted to share it with you.

So, this is the first time I’ve actually said anything about it all in any sort of capacity on this page (since I’m assuming most of you came from my page), but I am transgender.

I never really brought it up before because I never really thought it was relevant to a lot of the conversations I was looking to have when I first started out, and, frankly, I didn’t say a lot about it because I was scared. I was scared of rejection and hostility, so I was hesitant, and I’d only told one other person in this entire community for as long as I’ve been on her, but after more than half a year running this account, I feel like I trust this community and all of you people that I love so much enough to fully come out. (Although, granted how often I post about transgender characters and representation, this might not be as big of a surprise as I’m thinking).

And the reason I bring it up now, is that to understand how I look at the Crucible, how I see it through my lens, comes entirely from that perspective. They say all media is subjective, and your life experiences will shape how certain stories and moments hit you, and this one hit all the right notes for me.

Because reading this issue, I felt like there was a lot from Melody’s perspective that I could identify with personally. I’m not saying every transgender person would feel the same, it’s strictly from my own experience, but I feel the story had a lot of strong transgender parallels.

Granted, this is not unexpected from the X-Men who have always been a great metaphor for any group that has ever been “othered” in society, whether it was based on race or gender or sexuality. To me, understandably, their parallels with the LGBTQ community have always been the ones that have spoken the loudest.

When it all comes down to it, Melody’s journey into the Crucible, in to do this “insane” thing that feels so against norms, feels like my transgender journey. I go back to a line that Exodus dropped during the campfire scene when he equates being a powerless mutant to being “trapped in a body that is a prison.” Melody’s willingness to dive headfirst into the Crucible, without hesitation, is because she knows who she is, who she can be, and who she wants to be. Because she doesn’t want to feel trapped in her own body. So she goes, and stands face-to-face with an insurmountable foe, all for one goal.

Apocalypse answers her name, and she gives the one she claims, but he tells her to use the one she was given. And she fights for it, it leaves her broken, bloodied, but she still stands, because it’s what she wants. What she needs. She knows who she is, and she’s willing to do anything to get it.

And that feels a lot like the journey I’ve experienced. Going through life, wishing that something was different, but still existing. Then, finding out that there was a way to fix things…to make everything right, but it would be hard…it would be to go against convention. You could choose not to, as Apocalypse said, “It’s an existence, of sorts. There’s nothing wrong with it.” But you have to ask yourself…is it worth it?

I’m in the middle of that journey right now, at the beginning, really, and I just realized that I am in my own Crucible, right now. I made my choice, at any moment I could give up, make it easier on myself…make the pain that’s already come…and the pain that’s yet to come stop. It’s been tempting. Coming out to my parents wasn’t awful…but I think we still have a long way to go, and I don’t think it’ll go much better with my extended family. My uncles and aunts, my grandparents and cousins…and I dread to think about old friends I knew, because I grew up in a very conservative town…and I know that when they find out…it’ll hurt. So I could stop now, let everything go back to the way it was, no one would know…

Or I could keep going. Fight through the pain, fight for the life I want to leave, no matter how much it hurts, no matter what I lose. To be born again, and to be honest with you it does feel like part of me has to die to make that happen. But in the end…I’m still here.

So while it may feel extreme, the measures taken in this issue, I think I love it so much because, from my view, there’s nothing extreme about it. If I was in Melody’s shoes, I’d take the chance in a heartbeat, too. Hell, with the prospect of a multi-year transition on the horzion I think Melody got off easy with the one and done, and the prospect makes me incredibly excited to see what the X-Factor team is going to be doing down the line since they said they were going to be dealing with transgender issues in a story arc down the line!

So, ultimately, while I get where this story can be a bit frightening in its concepts and with just how different it is, I think that there’s so much wonderful discussion to be had! Obviously, I went on for like 5,000 words about it…and I think that re-reading this has sold me, completely, on the new Dawn of X. Because if Hickman can keep making us ask crazy questions like this, and keep tackling such unique and extraordinary situations…I think this run has all the potential in the world to be one of the greatest comic runs of all time.

And I know I’d take that same chance as Melody because I already did, and every day I feel like I’m standing there with my sword…looking Apocalypse in his face…

And every day, he asks me if I want to stop….

And every day, I’m going to do the same thing…

I’m going to tell him to go to hell.

-Anne

I love this! Thank you for sharing your story and your lens for this amazing run of comics!

LikeLike